The Brutalist is a highly sensory film, the kind that seeks to maximize the impact of film’s potential to engage our eyes, ears, and touch. It uses all the tools in film’s repertoire to convey its time and place both literally and figuratively as we move through the landscape of protagonist László Toth’s struggle. László’s internal conflict and the conditions he lives in alternately shape and reinforce one another in a reciprocal bending and breaking. László himself attempts to build things out of the momentum of this process, creating, as his niece Zsófia describes, works with “an immoveable core … they indicate nothing. They tell nothing. They simply are.” László’s architecture, then, is a manifestation of incorruptibility.

László is a complicated figure: he has been viscerally wounded by life, and his efforts to ease the pain of those wounds are insufficient to heal them. Nevertheless, he possesses a deeply rooted dignity. This dignity is most apparent when he is immersed in his work, and he staunchly defends his designs from outside manipulation. His outright refusal to have his art bastardized by those with less or no vision is incompatible with the capitalist American system and the attitudes and sensibilities it produces. But the tempests of the 20th century have caused enormous upheavals across the world, and László’s life is one of the millions caught in their waves and fighting just to stay above the water.

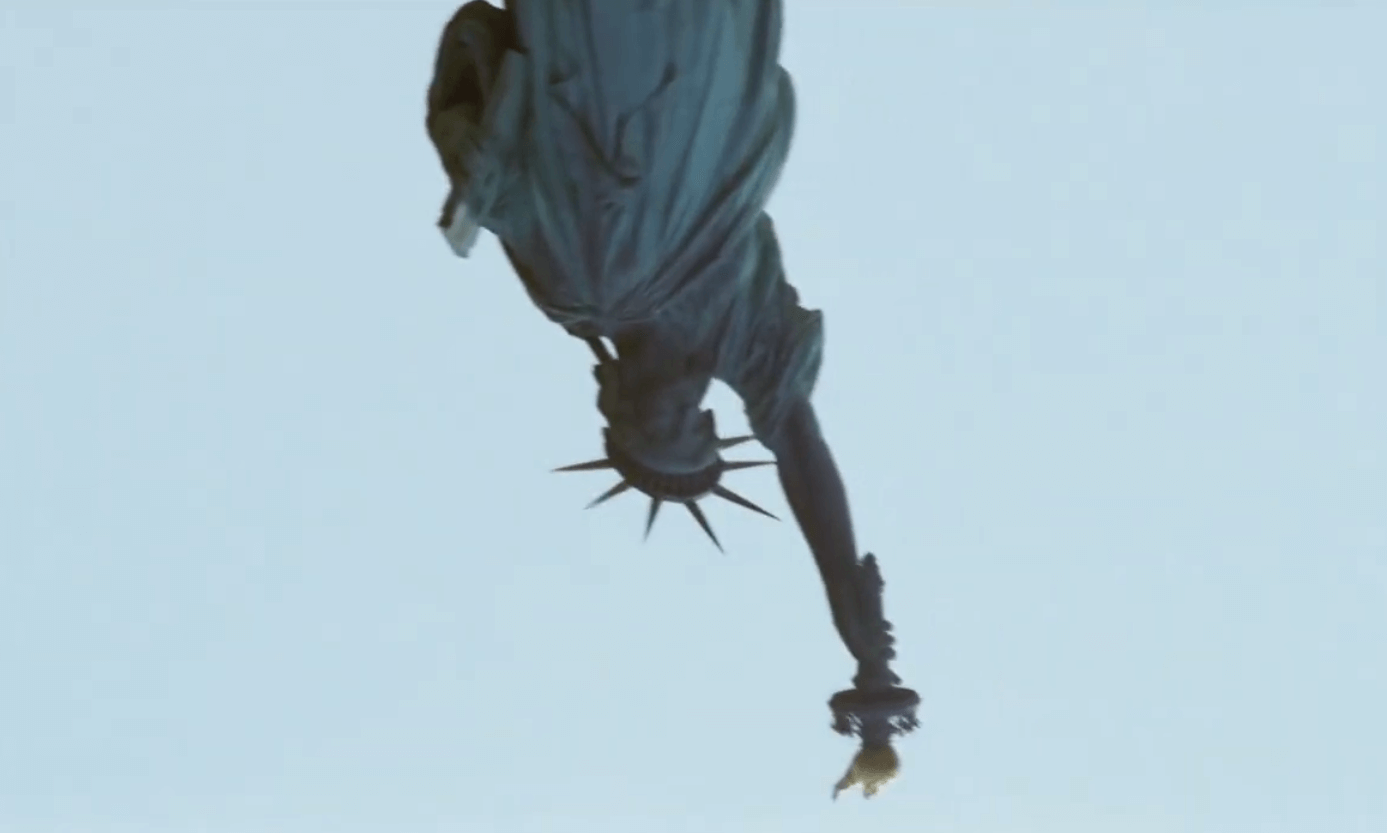

Originally from Hungary, László has already completed his training at Bauhaus and survived the Buchenwald concentration camp by the time the film starts. His arrival in the United States is inaugurated with the quintessential symbol of the American Dream materializing before the huddled masses: Lady Liberty and her eternal torch. Yet she is upside down, perceived from a sharply low angle, looming above him like an untouchable God.

The promise of the American Dream is not what attracted László in the first place. He is in the United States because, quite simply, he has no other options and—or so he initially believes—no other living family members besides his cousin Attila, who has settled in Philadelphia. Budapest and Europe have been destroyed in the war, and Europe’s Jewish population has suffered an active campaign of extermination. The continent has been the site of a nightmare László has only barely woken up from. Now, it is enough for him to survive.

But for the artist, even just surviving is a struggle in a system so fundamentally grounded on capital and consumerism. László’s designs are lofty, sophisticated, pure; his audience is earthy, simple, competitive. When he completes his first project in the United States—the remodeling of a personal library in the home of Harrison Van Buren, a business magnate who has made his millions (not coincidentally) in manufacturing during the war—Van Buren throws László and Attila out of his home in a rage, and Van Buren’s son Harry, who commissioned the project, refuses to pay.

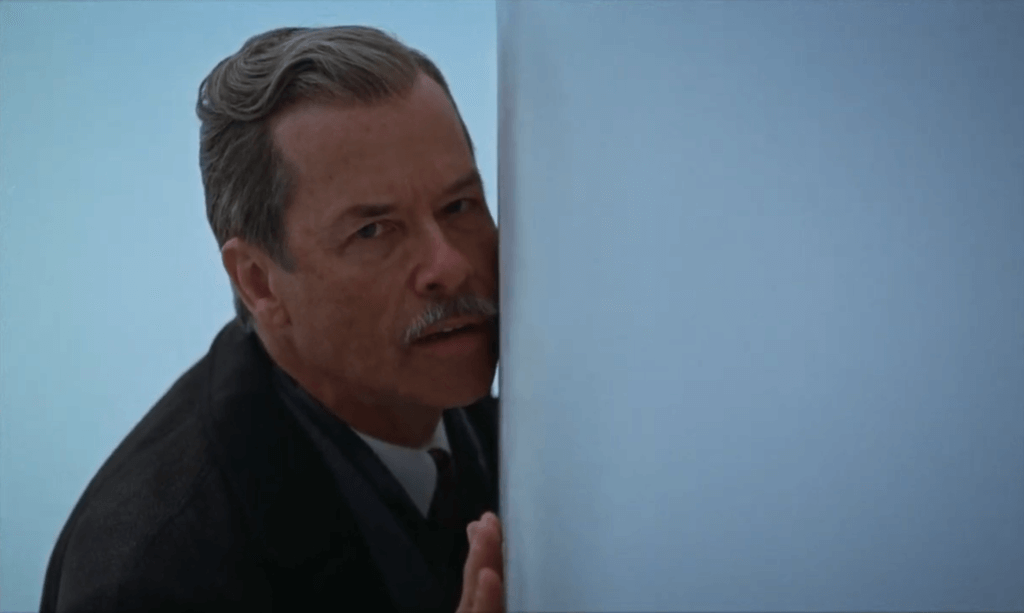

Later, after Van Buren’s new library brings him a feature in a magazine celebrating him as a “forward-thinking man,” he commissions László to build a community center. In this endeavor László must contend with the intrusions of Leslie, a local contractor, and Jim Simpson, a low-grade architect, as they attempt to implement practical cost-cutting measures to what they perceive as László’s “bizarre” design. László also has to try to appease Van Buren himself—who envisions a grand, omni-functional building for the public that is really a celebration of himself and, oddly, his mother—as well as the local community, which is largely Christian and unworldly. But László’s placation of those around him is limited to words only; he refuses to compromise his design.

Van Buren revels in his position as a patron of the arts, and he declares more than once to László that he finds their conversations “intellectually stimulating.” For Van Buren, a man with enormous wealth and a clear desire to appear cultivated, László becomes a fetishistic object of envy and admiration. He is jealous of László’s inherent artistry and dignity, even as he degrades him as a “societal leech,” and he desires to redirect that artistry into creations that vaunt him and to break László’s into submission. He seeks to dominate. The prostitution of the artist as an inevitability in a radically capitalist system is thus something Van Buren participates in both figuratively and literally. In this regard, the artist parallels the immigrant; László is both, and therefore doubly damned.

While this dynamic brings László immense suffering, he is fortunate to have in his wife Erszébet the same immovable core that he seeks to achieve in his buildings. The film itself is likewise a rejection of the “rules” films are supposed to follow for strong commercial appeal. It was made on a relatively small budget of $10 million, and it has a runtime of 215 minutes—far beyond the standard 90-minute feature length. The film also renders its acts visible to the viewer, with the breaks depicted using title cards. Its structure, propelled by a sometimes melancholy and sometimes explosive score, includes a built-in intermission. The score builds on itself, incorporating diegetic sounds, rhythmic pulsing, feverish glissandos, brassy marches, mechanical metronomes, piano that softly reaches and drops like rays of sunlight.

And this brings me to what I admire most about The Brutalist: it is so successful in its use of sound and image that one could listen to the soundtrack on its own or watch a montage of its images and understand the story being told. The focus on textures, in particular, is striking. The film is built on textures. Light is at times blinding, at times buttery, at times sacred. The sky is a blanket. The rich are tailored and sleek, the poor woolen and grizzly. Jewelry is an arrangement of metals and stones. The earth is malleable and mineable. The city is cemented, industrial, and hungry for more. Leather is taut and functional, smooth and natural. Skin is soft and bruisable. Concrete is hard and sturdy. Marble is impenetrable.

The spaces László occupies for much of the film are spartan, and his designs are similarly sparing. The focus is on materials and textures, the way they shape light and shadow, the way they guide movement and the eye. The materials, the spaces, the textures are the story, as it is and as it should be.

Copyright © 2022 My Sunset by Bogdan Bendziukov.