When I was first told about Baby Reindeer, it almost sounded like it could be sexist—in both directions—as a comedy based on the idea that a man being stalked by a woman is a suitable premise for something funny. For men, it might suggest that a man’s failure to overcome and manage an obsessive woman reflects his inability to assert himself, a key tenet of popular masculinity. For women, it might suggest that the very notion of a dangerous woman is laughable, that women cannot be taken seriously enough to be considered a threat.

When I watched the series, I realized I had misunderstood. Baby Reindeer invites us to let go of the notion that we have the right to expect others to behave in a certain way, to manage their problems the way we think they should manage them. We are made to sit back, be quiet, and listen as protagonist Donny works through his issues in his own way, the way that he needs. The series carefully undermines our assumptions and expectations, challenging us to reconsider how much we judge people for decisions they make when we lack the context to understand their motivations, fears, and hopes. Episode by episode, we are made aware that when we judge people, our judgments are informed by our own assumptions about them. These assumptions reflect more of who we are than the person we judge.

Donny is an aspiring comedian who attracts the attention of Martha when he offers her a free cup of tea at the pub where he works in London. The first thing he shares about Martha is that he “felt sorry for her,” which he goes on to describe as a “patronizing, arrogant feeling to have for someone you’ve only just laid eyes on.”

The reversed positioning of the male protagonist and his female pursuer/persecutor is used to both comedic effect and shock. This is where the series’ genius lies: it is funny until, very abruptly, it is not. It is unafraid of dipping into the expectations that condition what we find amusing and then turning them on their head, taking them to extremes that force us to confront the inconsistencies, the presumptions, the cruelties that underlie them. These reversals between moments of laughter and moments of deep discomfort are sudden, forceful, almost nauseating as pleasure is upended by alarm.

Further complicating this dynamic is the fact that the show is inspired by writer and actor Richard Gadd’s actual experiences being stalked following traumatic experiences of sexual assault. The story is unpacked little by little, with hints dropped in the first few episodes before Donny (whom Gadd plays) is obligated to dive deep into his past to try to make sense of why, despite the obvious dangers she poses, he is so attracted to Martha. Her fixation is clearly unhealthy, yet he cannot bring himself to give it up.

Donny is laden with shame, and it is this weight which drags him down to a place where he not only chooses not to ask for help but in some ways doesn’t even want it. He is ashamed of his lack of success as a comedian. He is ashamed of his abuse at the hands of another writer who grooms him, casting him promises of opening doors that keep him returning to the abuse. He is ashamed of having such a deep-seated desire for validation that he will allow himself to be used in this way. He is even more ashamed when that validation does not come and he is left with nothing but the pain of the abuse and an inability to be intimate.

Donny is also desperate for validation, but he is terrified of being seen by others, that they might perceive him as the failure and coward he feels himself to be. And so, when Martha walks into the bar, Donny feels sorry for her because he perceives in her the same desperation he knows he has but hopes that others don’t pick up on. He feels that the person before him is in an even more pitiful state than himself.

Yet Martha sees Donny somehow, and she feels seen by him. His offering her a cup of tea is the moment that ignites this. The editing underscores their mutual recognition through the numerous shots lingering on their gazes at one another, usually in mid-shots and close-ups, especially close-ups of Donny’s face.

As their relationship becomes progressively more dangerous and Martha reveals herself to be increasingly unhinged, Donny contends with the decision to pursue legal action against her. Over and over again, he puts this decision off. It is only when Martha threatens those close to Donny—first physically attacking his girlfriend Teri and then harassing his parents—that he actually seeks help from the police. But even after Donny has Martha officially charged and sent to prison, he continues to return to her messages, which he has meticulously categorized according to mood. In some, Martha babbles about her day, in others she waxes on about Donny’s attractive qualities. In all of the messages, Martha is unapologetically herself, searingly vulnerable.

Vulnerability is the beating heart of Baby Reindeer. It ties Donny and Martha together. It is what Martha perceives in Donny and alternately cherishes and chastises him for. It is why Donny cannot punish Martha. He recognizes that there is something broken in her, just as he fears there is something irreparably broken inside himself. When he first meets her, then, his sympathy for her is composed of both compassion as well as dismissiveness. That same compassion is something he doesn’t grant to himself, while that same dismissal is something he fears. When Donny finally reports Martha and attends her hearing, he muses, “I really couldn’t tell whether it was putting an end to her fascination or to mine.”

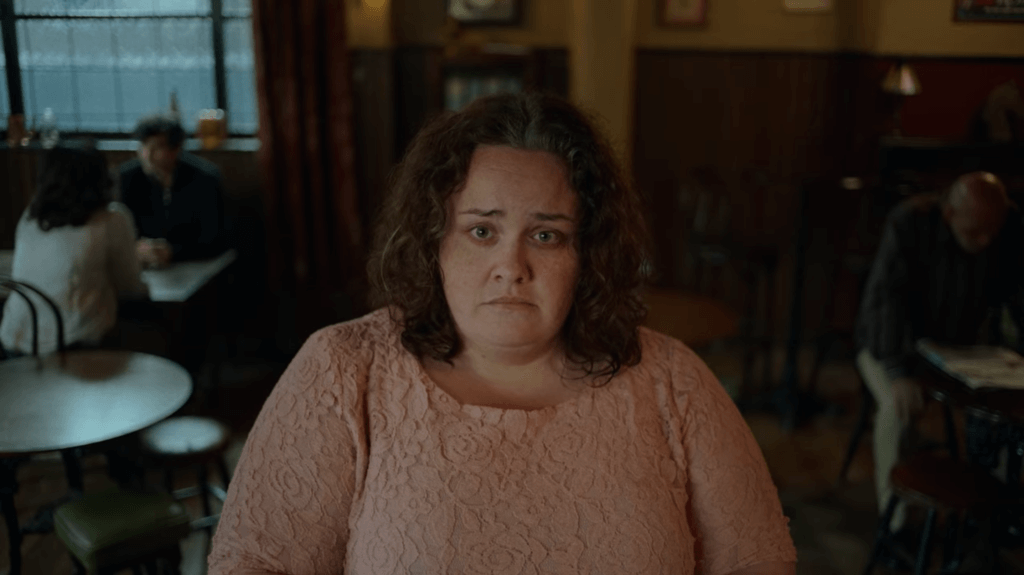

When he later sees his abuser again and is distraught by their interaction, he seeks comfort in Martha’s countless voicemails. As he sits down in a pub, drowning in an oversized yellow parka and with a gaunt face, Donny opens a previously unheard voicemail. Martha’s voice recalls her past trauma and Donny’s similarity to a toy she cherishes as “the only good thing about [her] childhood.” Donny begins to sob, recognizing that he has participated in further hurting Martha. He understands that she is a victim who has suffered just as he has. The bartender serves him his drink and Donny, attempting to recover himself, realizes he has no wallet. Feeling sorry for Donny, the bartender offers the drink on the house.

Gadd engages in a degree of self-exposure by sharing his story that is nothing short of breathtaking. The abuse that Baby Reindeer depicts is often treated as unspeakable in public discourse, but the series talks through the complex web of feelings that abuse sows. These feelings—frustration, confusion, embarrassment, betrayal, shame—take root and continue to grow into unexpected challenges long after the abuse is over. Gadd plumbs the psychology of trauma and the ways it contaminates the ability to maintain healthy relationships with others as well as oneself. He reflects on complex, uncomfortable questions about sexuality and intimacy and how these can be conditioned by abuse. And while the show is funny at times, it is also heartbreakingly honest in its quest for answers that ultimately remain elusive, and heartbreakingly determined to ask questions anyway.

Copyright © 2022 My Sunset by Bogdan Bendziukov.