It was an ambitious venture to try creating a new dinosaur-themed film unrelated to the gatekeeping behemoth that is the Jurassic Park franchise, which has monopolized the dinosaur flick since the first Jurassic Park film basically founded the genre in 1993. Writer-director duo Scott Beck and Bryan Woods were obviously aware of the dangers of crossing too closely into Jurassic Park territory and instead infuse this film with the tropes and aesthetics of space and horror films. Yet there is something (actually, several things) about the result that just does not work. This raises an interesting question: to what extent is it necessary to adhere to the viewer’s expectations of how a genre film—in this case a dinosaur film—should look and feel in order to make the film successful?

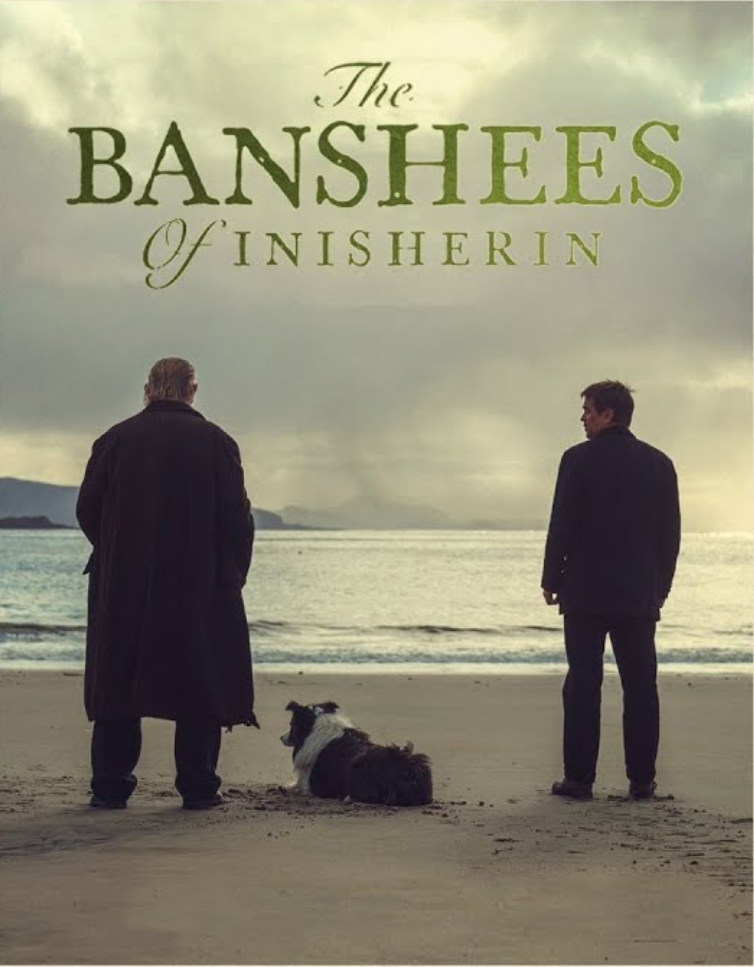

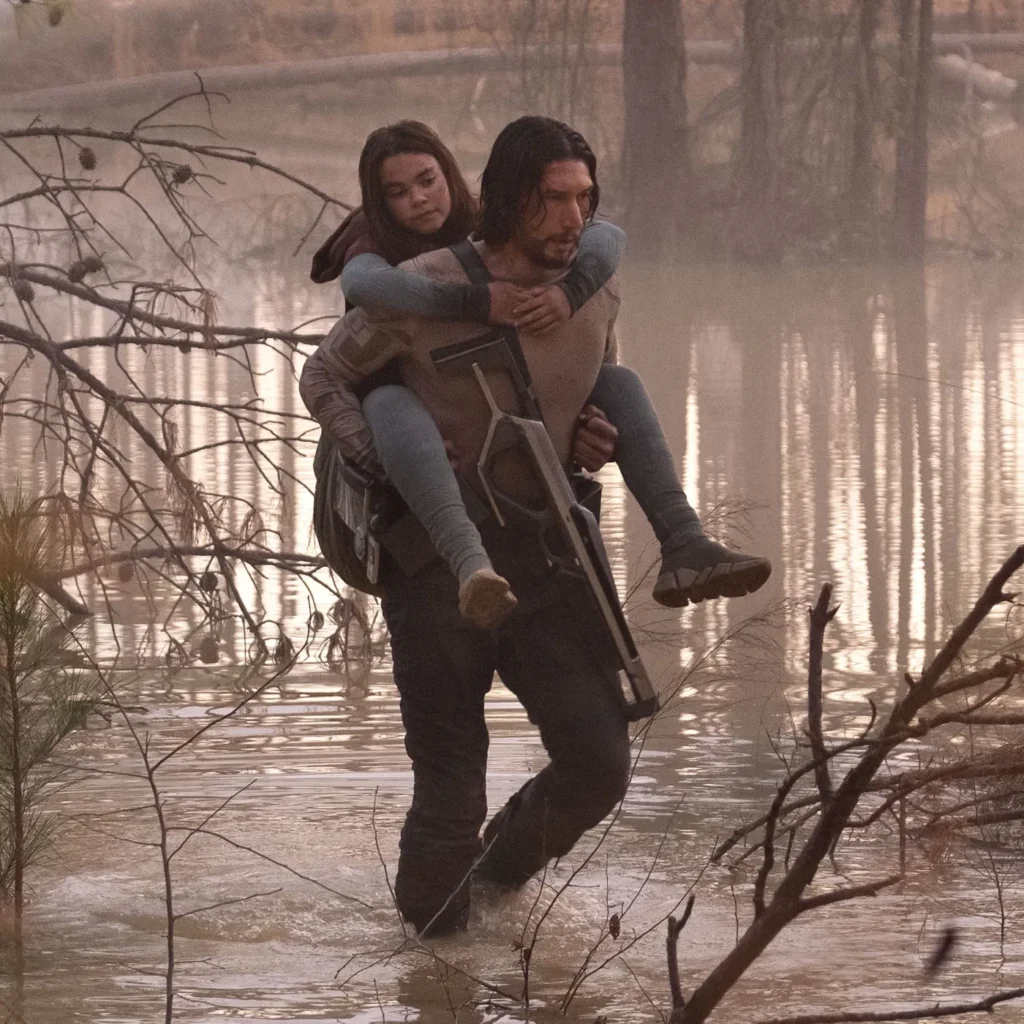

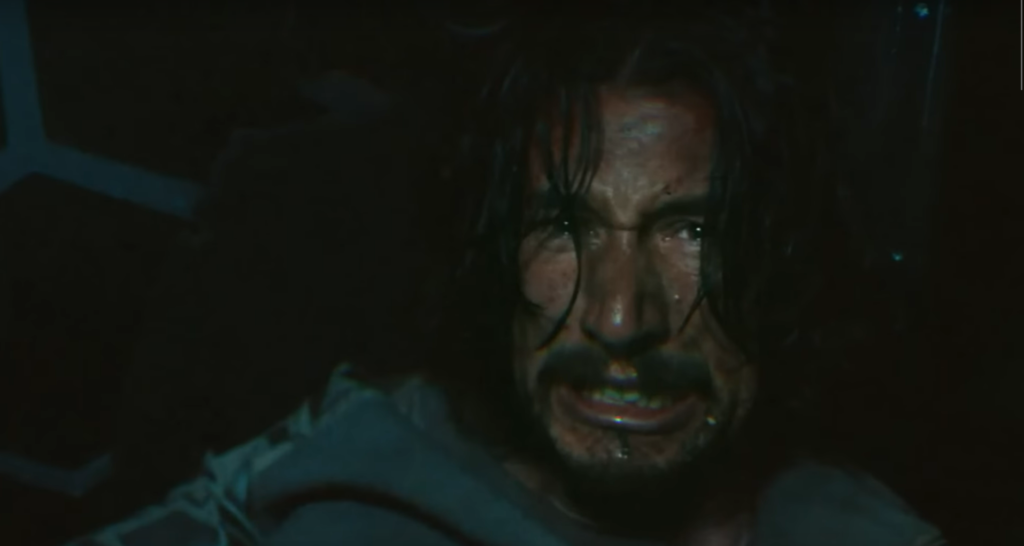

65 has an opening crawl reminiscent of Star Wars; this is just about all the context that is given regarding the premise of the film besides a few throwaway lines about a third of the way through. In essence, Mills (Adam Driver) is a spaceship pilot who undertakes a two-year exploratory mission to pay the medical expenses of his sick daughter. One day while Mills is sleeping, the ship encounters an asteroid belt (whoops) that bangs it up and causes it to crash-land. In the process, the ship breaks in half, and the bevvy of pods holding (one would have assumed) scientists in a cryogenic sleep tumble out, killing everyone. Mills, lucky devil, survives with nothing more than a cut to his abdomen, which evidently is very painful but—by some unexplained miracle—does nothing to limit his freedom of movement over the days to come. Obviously, Mills is no mere man, because he makes a similarly instant recovery later when he dislocates his shoulder after tumbling 20-some feet and then immediately takes down a herd of bloodthirsty dinosaurs with underbites.

Anyway, Mills resigns himself to dying on this strange planet, but he changes heart when he discovers that there is a 9-year-old girl, Koa (Ariana Greenblatt) who has survived the crash with him, and he needs to get her home. Their relationship is rocky at first because otherwise viewers would get bored and there needs to be some semblance of character development over the course of the film. Indeed, Koa goes from being an animal-loving child who risks her life to pull a baby dino out of some tar to a fearless warrior who stabs a T-Rex in the eye with a tooth by the end of the movie. Pretty impressive for a 9-year-old.

In the backdrop of all of this, the literally Earth-shattering meteor destined to wipe the dinosaurs out is about to hit the planet (“Catastrophic event detected,” Mills’ scanner tells him with monotone robotic concern). So, if being eaten by dinosaurs weren’t enough of a plotline, Wiles and Koa also face being vaporized due to a meteor strike.

Mills and Koa have little communication because Koa does not speak English, which places significant limitations on the exposition of how what is happening is possible. The choice to limit dialogue in this way can in the best-case scenario be viewed as an effort to explore other means of characterization and storytelling; in the worst-case, it is simply lazy filmmaking. I suspect the latter. The directors probably realize that Koa’s presence on the spaceship makes no sense, so they—and, by extension, their characters—just choose not to address it.

Besides the pitfalls of the screenplay itself, the dinosaurs in this film are distinctively slimy, crawly, and creepy. While the special effects are in and of themselves up to scratch with what viewers expect from CGI, the choice to portray the dinosaurs in this way makes them seem more alien than animal. They have sinuous movements which are noticeably different than the jerkier, almost spasmodic approach taken in the Jurassic Park films that was presumably informed by an interpretation of dinosaurs based on their modern-day descendants, birds. Their skin is viscous, which also does not seem scientifically accurate—another element that the Jurassic Park films have generally tried to honor—but is pretty gross to watch.

Scientific or historical accuracy are far from obligatory in filmmaking and are likely more often the exception rather than the rule. Still, the aesthetics of the dinosaurs in 65 are disorienting because they stray so far into the monstrous and alien. This does not really matter for a film that pretty clearly seeks to keep its audience’s attention through loud bangs and jump scares rather than engaging storytelling, but it is one more reason that 65 fails to secure a place in the dinosaur film canon dominated by Jurassic Park, which does a lot more work on the narrative level (albeit in some of its films more than others).

Of course, the Jurassic Park movies are not the only dinosaur movies that exist. A few obvious alternatives come to mind, such as any of the number of animated children’s films featuring smiley talking dinos (I’m looking at you, Land Before Time) to the more rustic depiction in the loincloth-laden One Million Years B.C. Dinosaurs also make an important appearance in the various iterations of another big franchise, King Kong, not to mention whatever Godzilla is supposed to be. Still, the fact remains that Jurassic Park has become the cornerstone of the genre. There have not really been any other films that have even tried to chomp their way into its territory.

On a personal note, I was painfully disappointed by 65 not because it is different than Jurassic Park but because it is just a badly written film. I was actually very excited that a non-Jurassic–Park dino flick was coming out; like any good 90s kid, I was obsessed with dinosaurs. I consumed a steady diet of dinosaur content that included not only Jurassic Park and Land Before Time but also Walking with Dinosaurs, Dinosaur Planet, and the Dinosaurs TV series. Heck, I even begged for the dinosaur egg Quaker oats for breakfast and had a stegosaurus piggy bank.

In other words, I am game for anything prehistoric and am predisposed to be into it because of nostalgia.

Still, the influence of Jurassic Park in particular on what we as viewers expect to see when we buckle in for a dinosaur adventure cannot be underestimated. Generic conventions have been crafted, honed, and reinforced by each successive film in the series: from the way the dinosaurs look and move—which, though evolving over the course of the 30-year franchise in accordance with both new knowledge and technology, has remained consistent—to the (waning?) intelligence of the plotlines that raise timely questions about the implications of scientific progress. The franchise has molded each aspect of the genre, so a film that only somewhat follows that formula runs a big risk of failing to satisfy what viewers are interested in seeing.

That is not to say that filmmakers should not be trying to break the Jurassic Park mold; it is just that any film that attempts to do this needs to be so well done that it awakens a new sensibility and desire for a different type of story. 65, alas, does not achieve this.

Copyright © 2022 My Sunset by Bogdan Bendziukov.